Vol. 15: The Phenomenon of Craving

Did I ever tell you my son is a milk junkie?

Like, utterly and wholly strung out on the stuff.

And not soy milk, the almond milk I prefer, or even milk with only two percent milkfat, but the richest, creamiest cow-mother-nectar known to man.

Despite my best efforts, he begs for his daily dose of dairy, jonesing for more, and is most certainly of the carton half-empty camp.

The kid has it bad.

Craving may as well be an emotion; I've felt it, and it hurts.

Once upon a time, in my early days of attending 12-step meetings, an old-timer asked me if I considered myself a real alcoholic.

He explained, "See, if you're the real deal, you've succumbed to the phenomenon and proved yourself insane."

My look of confusion relayed my stultification, so he suggested I open my Big Book—A.A.'s basic text—and read The Doctor's Opinion section.

I did as the gruff man recommended, and suddenly: Eureka!

I had myself all figured out; you too if I'm being honest.

Not only that, but I could use this doctor's brilliant exposé as a testimony to my faltering friends and family members:

"I'm not morally inept, just batshit crazy, folks! The good doctor said so!"

PAGING DR. SILKWORTH

For those relatively uneducated on the history of alcoholism, there was a time when the alcoholic was considered more or less insane. Alcoholics who didn't wind up in prison received treatment in asylums, and those who treated them had little hope for recovery.

The idea was that confinement would force these people to become sober while making them fear punishment and move them into abstinence; however, this was not the case.

Instead, once released from incarceration, many individuals punished for their inability to control their substance abuse activity quickly returned to their previous drug of choice.

Most of society couldn't understand why these people were returning to the substance despite knowing the consequences they were likely to face.

In short, there was something more to drug and alcohol abuse, forcing people to defy their logic by behaving in ways that contradicted what would have otherwise been in their best interests.

Then came a physician, William D. Silkworth, M.D., whose opinion of alcoholism increasingly differed from that of his colleagues. Hence, he comprised his thoughts into two letters strategically placed as a prologue to A.A.'s Bible.

In his first letter, Dr. Silkworth details his experiences with one of his patients, a drunk named Bill W., who opened the doctor's eyes to a possible path toward lasting sobriety.

But the introduction chapter's final half—letter number two—is the discourse that hit me where it hurts, especially this part:

Men and women drink essentially because they like the effect produced by alcohol. The sensation is so elusive that, while they admit it is injurious, they cannot, after a time, differentiate the true from the false. To them, their alcoholic life seems the only normal one. They are restless, irratable and discontented, unless they can again experience the sense of ease and comfort which comes at once by taking a few drinks—drinks which they see others taking with impunity.

After they have succumbed to the desire again, as so many do, and the phenomenon of craving develops, they pass through the well-known stages of a spree, emerging remorseful, with a firm resolution not to drink again. This is repeated over and over, and unless this person can experience an entire psychic change there is very little hope of his recovery.

Dr. Silkworth's second letter is essential for several reasons, primarily in how it approaches the disease model of addiction. While his first letter praised the spiritual remedy, his second letter gears its focus toward the physical and mental components of the disease.

Those who refer to alcoholism as an "allergy" are, whether they know it or not, more or less referring to the theories proposed by Silkworth in The Doctor's Opinion.

This allergy produces indescribable symptoms and is very similar to any other allergy one may have. For example, if you are allergic to peanuts, you may experience red welts on your skin, difficulty breathing, or tightness in your chest.

This allergy consists of two parts—the physical craving and the mental obsession. According to Silkworth, it is generally best to address the physical component first.

INSANE IN THE MEMBRANE

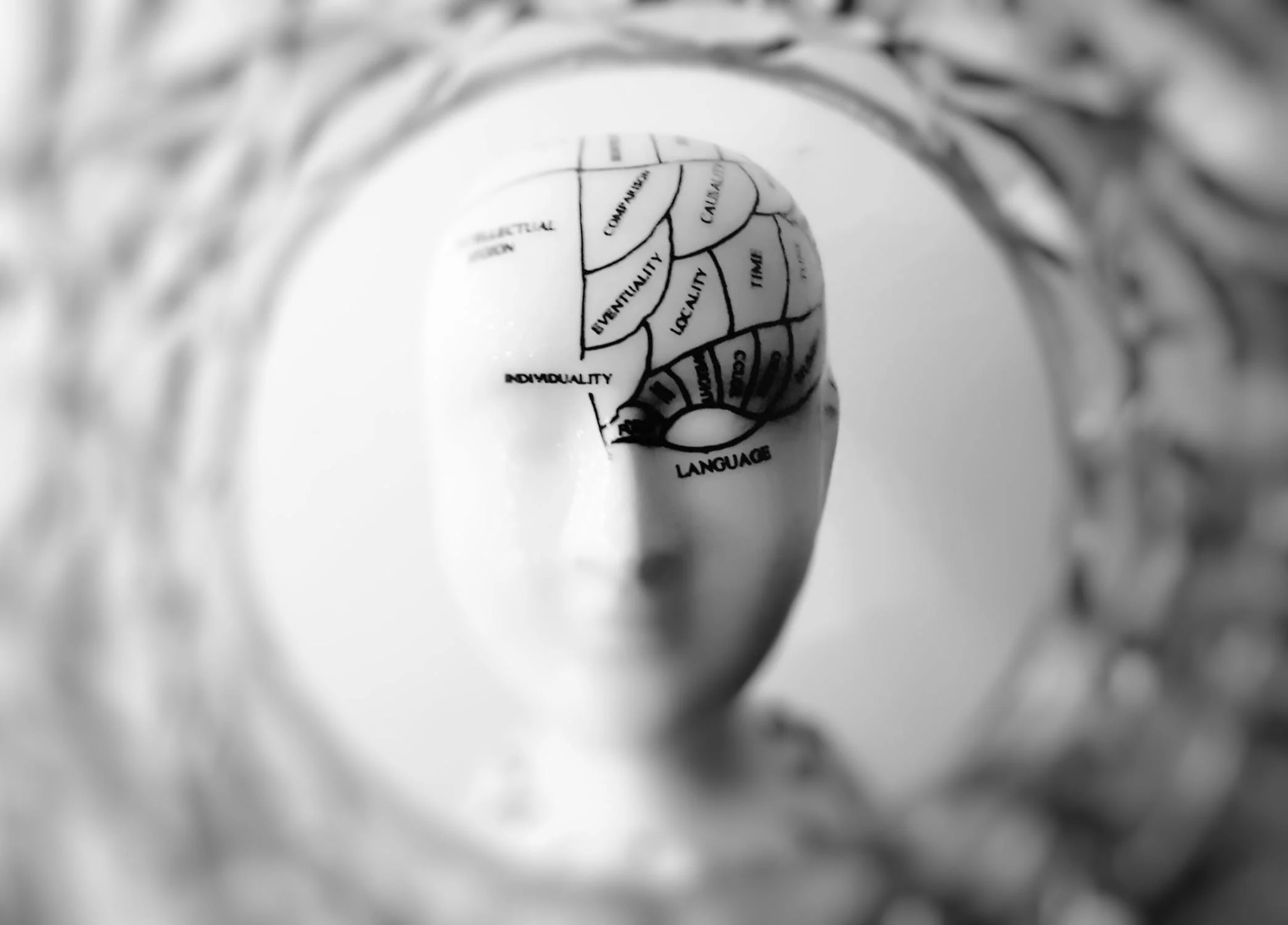

Researchers are only now beginning to understand the mechanics of craving. At its most basic, Merriam-Webster defines the phenomenon of craving as "an intense, urgent or abnormal desire or longing for something."

According to Purdue University psychology professor Stephen T. Tiffany, craving was historically viewed as a condition—a biological, "primitive motivational" state.

But recent research by cognitive behavioral psychologists and scientists indicates that craving is "a complex, multi-dimensional process" involving "higher-order mental functions."

Simply put, craving is complicated—it involves many parts of our brain and biology. It is both behavioral and physical, and therefore not like a light switch one can shut off—but there are things you can do to keep it in check.

Cognitive behavioral specialists have a few theories that they are studying, but anyone living with addiction knows that the phenomenon is pretty basic in real life. First, you have that fierce, urgent desire for drugs or alcohol. Then, the passion becomes all you can think about— it hijacks your mind, overpowers your need for anything else, and overrides your intention to stay clean.

More than a century ago, Merck's Manual recommended cocaine to eliminate the craving for alcohol, characterizing cocaine as a substitute for alcohol to be used whenever the urge occurred.

Later, craving became a term used for patients affected by addiction to other drugs, and over the following years, several definitions were formulated, showing many dissimilarities.

For decades, people erroneously considered a craving a symptom of alcohol withdrawal. However, several studies show that alcoholism-related compulsion can appear after long-term abstinence, typically provoked by the first drink or situations associated with alcohol use.

At its core, physical craving is a phenomenon in the brain that, when activated, creates an intense yearning to use the addictive substance or do the addictive behavior.

Essentially, cravings are a symptom and shouldn't be confused with feelings of wanting or liking something; for example, when I tell my husband I'm craving tuna tataki from the sushi joint across town.

Over time, substance use adversely affects our neurocircuitry, and our brain receptors become overwhelmed. The brain responds by producing less dopamine or eliminating dopamine receptors—an adaptation similar to turning the volume down on a loudspeaker when the sound becomes too noisy.

The physical and emotional sensations of cravings vary from person to person and substance to substance. Some experience feelings of excitement, like rapid heartbeat and flushed skin. Some feel shaky and experience intense longing. For other folks, cravings manifest as a vivid flashback to active addiction.

Once we begin a recovery process, we may think that after a week of being completely clean and sober, we are experiencing cravings for drugs or alcohol again, but what we are undergoing is the mental obsession that happens after the craving occurs.

It's the erratic, racing thoughts of when you'll get your next fix, how much of it you'll use, and how much you'll stash away for later. Calling it a craving can trick our minds into thinking we're doomed to fail again.

When we name it a mental obsession, we can see it more easily for what it is—and realize that it will pass soon enough. However, the physical allergy we feel will never go away, no matter how long we abstain from drugs or alcohol. If we decide to use again after months or even years, we'll be right back where we left off; it's the mental obsession we can fight in recovery.

MAKING FRIENDS WITH THE URGE

There are many avenues to choose from when searching for healthy methods of overcoming mental obsession and powering through debilitating physical cravings. However, the most important thing I've learned thus far is to trust the process.

While it is clear that the scientific study of craving has advanced substantially over the past three decades, it is equally valid that we have a long road ahead.

Advances in assessment, neurobiology, genetics, and contributions from learning theory and pharmacotherapy have been exciting. However, treatment approaches have been only moderately effective.

If we are to enhance the treatment for craving, we must emphasize the application of scientific findings.

Integrating several important factors is necessary for understanding craving neurobiology and its role in addiction maintenance and recovery.

For instance, the role of brain development in the expression and maintenance of craving is an important area of investigation. In addition, a recent study of adolescent heavy drinkers found that increased brain responses to alcohol cues (measured using fMRI) decreased over a one-month abstinence period, thus highlighting the malleability of teenage brain function.

To that end, much remains to be uncovered from the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, the most extensive long-term examination of brain development and child health in the USA.

These findings, in turn, can be translated into a complete understanding of addiction as a brain disorder and uncover tractable avenues for intervention to bolster addiction treatment's overall efficacy.

In the meantime, as you continue your recovery journey, remember that recovery is a marathon, not a sprint. Many long-term recoveries depend on finding out what works for you. So, continue attending meetings and therapy and implement additional strategies to help strengthen your recovery.

Be gentle with yourself on your journey. It usually takes numerous trials to find what best works for you. There are no failed attempts. Any attempts to manage cravings, even if they are not successful, are essential learning experiences.

Search for new learning about craving triggers and what works or does not. Then, use this knowledge to manage the next craving that shows up. You may have heard of the saying, "Rome was not built in one day," and for most of us, managing cravings and changing our behavior takes practice and many attempts.

It is typical to have mixed feelings about managing cravings. Feeling ambivalent about giving up an addiction is normal; food, alcohol, drugs, or sexual attention may have given you comfort for a long time, even if they have been destructive in your life.

The desire to stop engaging in addictions and the anxious sadness about the changes involved usually happen concurrently.

Being ambivalent about giving up an addiction does not mean you can't do it.

Cravings are a natural part of living. We all experience them, and it's impossible to live a thirst-free life. So the goal is not to get rid of cravings but to learn how to live with them.

We can move forward and live the life we want, even in the presence of cravings. It has been my experience that instead of running away from cravings, once I accept the company of desires in my life, I can begin to make peace and stop struggling with them.

We may not always have a choice whether or when a craving appears, but we can choose how to respond.

I'll leave you with a brief but powerful editorial my father wrote and shared with me after learning I wrote an article on one of his favorite topics.

It starts with a flash of excitement.

Brain buzzes, and heart pounds. It's like the whole body is saying YES.

Then the anxiety hits! I start to feel light-headed and shaky I want it so much. But I can't. But I want to. But I can't! I know I shouldn't, but I'm not sure I can handle this feeling without falling apart or giving in.

Welcome to the world of craving. Maybe it's a craving for a cigarette, a drink of alcohol, or a triple latte. Perhaps it's the sight of a last-chance super clearance sale, a lottery ticket, or a doughnut in the bakery window.

In such a moment, I face a choice: follow the craving, or find the inner strength to restrain myself. This is the moment I need to say "I won't" when every cell in my body is saying "I want." It's not some abstract argument between what's right or wrong.

Instead, it feels like a battle between two parts of myself, or what often feels like two very different people. Sometimes the craving wins. Sometimes the part of me that knows better, or wants better for myself wins.

Which version of me wins this battle is a mystery.

One day I resist, and the next time I give in!

THIS WEEK’S LINKS:

Post a comment